Night shift on the reef

There are nocturnal animals in the sea, just as there are on land. Many marine animals hide all day and only come out at night to hunt, feed, or mate.

There are nocturnal animals in the sea, just as there are on land. Many marine animals hide all day and only come out at night to hunt, feed, or mate.The colonial anemone pictured here (Nemanthus annamensis) is one such nocturnal marine animal -- part of the underwater 'night shift' that begins shortly after sunset and lasts until dawn. The only way to see these nocturnal marine creatures is to dive at night.

The anemones in these colonies open as soon as it gets dark. During the night they look like pretty flowers, with their tentacles extended to feed. When morning comes they fold their tentacles inward and each one of the 'flowers' turns into a tightly shut fist. While they are closed during the day they look like nondescript lumps, their nighttime beauty obscured.

The photo was taken during a night dive in the Red Sea, near Sharm el Sheikh, Egypt. If you click on the photo it will enlarge.

Background check: Same critter, different look

This was an experiment to see how changing the background changed the 'look' of the creature photographed. All three images on this page are of the same creature, but each photo uses a different background. (You can click on each of the photos for a larger view.)

This was an experiment to see how changing the background changed the 'look' of the creature photographed. All three images on this page are of the same creature, but each photo uses a different background. (You can click on each of the photos for a larger view.)The creature is a kind of Polychaete worm called a Bearded Fireworm (Hermodice carunculata). It's a very distant cousin of the earthworm (same Phylum). Those clumps of very fine hair-like bristles are called setae.

The setae look nice and fluffy in the photos, but they are not decorative. They are the Fireworm's defense against predators (and divers?). When something touches the venomous setae, they break off very easily and stick in the skin of whatever has disturbed them. The name "Fireworm" comes from the very nasty burning sensation caused by the venom in the setae.

[Note: Handling these guys can be very tricky and is not recommended, even while wearing gloves. The setae will break off and stay lodged in the glove fabric, only to be transferred to your skin later on.]

The first photo shows a Bearded Fireworm on a natural background, just as we found it. This particular one was photographed in the Mediterranean Sea at Konnos Bay, Cyprus, but we have seen this species in many other places.

They crawl around on sandy and rocky bottoms at shallow depths, looking sort of like big caterpillars or centipedes. We've also seen them in seagrass beds, hurrying to and fro, searching for a meal.

They crawl around on sandy and rocky bottoms at shallow depths, looking sort of like big caterpillars or centipedes. We've also seen them in seagrass beds, hurrying to and fro, searching for a meal.The largest Fireworms we've seen have been about six inches (15 cm) long, but we understand that they do grow bigger. Most often we have seen them as individuals, but occasionally we have seen groups of them devouring sea urchins, a rather creepy sight.

Can you guess what the blue background is in the second photo? Believe it or not, it's Jerry's dive fin! On the spur of the moment we decided to scoop the Fireworm onto the fin to see what it would look like on a blue background. If you look closely, you'll even see scratches on the fin.

Then we noticed a red encrusting sponge nearby. We dropped the Fireworm from the fin onto the sponge. He started to crawl away, but not before I was able to photograph him on the red background. I think I like the red background the best.

Then we noticed a red encrusting sponge nearby. We dropped the Fireworm from the fin onto the sponge. He started to crawl away, but not before I was able to photograph him on the red background. I think I like the red background the best.I do like the color blue, of course, but blue plastic hardly is a 'natural' background, so the red sponge just works better, visually. The contrast shows off the Fireworm to good advantage.

Moving a creature to a nicer, prettier background is an old trick in nature photography -- on land as well as underwater. I haven't done it too often, but when I have, I always try to return the photo subject to its natural setting.

I'm not at all sure that a Bearded Fireworm would voluntarily crawl onto this kind of sponge, so before we left, we moved the creature back to where we initially found it on some algae-covered rocks. It's only fair.

Picture this! -- Photographing the photographer

Recently someone asked us, "How come there are hardly any pictures of Bobbie on The Right Blue?" The answer to that question is that I've always been the one behind the camera instead of in front of it. As a result, we have very few underwater photos of me.

Recently someone asked us, "How come there are hardly any pictures of Bobbie on The Right Blue?" The answer to that question is that I've always been the one behind the camera instead of in front of it. As a result, we have very few underwater photos of me.Ever since we began The Right Blue, Jerry has been going through the thousands of slides we had stashed away, methodically looking for the ones that have a story. Several days ago he came across the one at right. Fortunately it was filed away along with the one below. Jerry scanned them both and passed the images to me to write about.

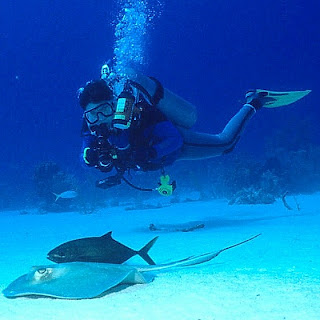

The first photo was taken by a dive guide and given to me as a souvenir of a trip we made to the Turks and Caicos islands. That's me, stalking my prey -- sneaking up on an interesting photo subject.

The second image is the photo I snapped a few moments later. I had followed this pair of critters around the sand flat for nearly ten minutes before they lined up just right for me to take the shot. I've mentioned in earlier posts that I really love to take pictures of critters' faces and especially their eyes. My next favorite theme after faces and eyes is behavior.

The dark colored fish in the photo is a Bar Jack (Caranx ruber). This fish makes its living as an opportunistic feeder, so it is swimming along a little above and behind a Southern Stingray (Dasyatis americana) hoping to snag a free lunch.

The dark colored fish in the photo is a Bar Jack (Caranx ruber). This fish makes its living as an opportunistic feeder, so it is swimming along a little above and behind a Southern Stingray (Dasyatis americana) hoping to snag a free lunch.The stingray rummages in the sand looking for little creatures to eat -- worms, small clams, tiny crabs, and such. To locate its prey, it fans away the top layer the sand by fluttering its wingtips.

The crafty Bar Jack follows closely, letting the stingray do the excavating. If the stingray uncovers something that looks tasty to the Bar Jack, the jack will snatch it in a lightning strike, then resume its position keeping watch over the stingray's shoulder, as it were.

We've seen Bar Jacks throughout the Caribbean. In addition to pairing with hunting stingrays, we've also seen them following goatfish -- another species that digs around in the sand and rubble for food.

By the way, the Bar Jack doesn't always look so dark. When it's not feeding, it is a handsome silvery blue color, with a black bar running along its back from its dorsal fin down to the lower lobe of its tail fin like a racing stripe.

Labels:

behavior,

Caribbean,

divers,

fishes,

marine life,

underwater photography

Current events, Part 3: Swept away

In the previous two posts I talked about currents in the ocean, and how much fun it can be for divers to ride currents. While drift dives can be wonderful, diving in currents also can create situations ranging from nuisances to something bordering on terror. This is especially so when the currents are unexpected.

One kind of current we don't like to encounter while diving is the downcurrent. Divers need to be in control of their position in the water column, and there are few things more disconcerting than to suddenly feel yourself being pushed down unexpectedly by a mass of water.

We ran into this situation one time while diving off West Caicos, in the Turks and Caicos Islands. Most of the dives in the area are 'wall dives' -- that is, along the face of cliff-like dropoffs. In this case, the top of the dropoff begins at a depth of about 20 meters, and the base of the dropoff is something like 1,000 meters straight down.

We ran into this situation one time while diving off West Caicos, in the Turks and Caicos Islands. Most of the dives in the area are 'wall dives' -- that is, along the face of cliff-like dropoffs. In this case, the top of the dropoff begins at a depth of about 20 meters, and the base of the dropoff is something like 1,000 meters straight down.

The walls there are glorious -- completely encrusted with fans, sea whips, and large sponges of many colors. The wall is the underwater edge of the land, and there's nothing beyond but the open water -- deep and inky blue.

It's quite common to encounter large sharks, rays, and other pelagic fish during wall dives, which is a big part of why wall dives are so appealing. On the other hand, since there is no bottom to land on, or even to use as a reference point, buoyancy control is important. (And, I might add, you definitely don't want to drop anything!)

On this occasion, we were drifting along the wall nearly 30 meters under the surface. We were nearing what had been planned as the deepest point of our dive, so we were carefully minding our instruments for air consumption and depth. We noticed that just ahead there were clumps of bushy sea whips that were fluttering downward. I mean not just hanging downward, but fluttering as if water was being poured over them from above. (See photo.)

I paused to take a photo, and Jerry continued along ahead of me. When I looked away from the camera viewfinder and back at Jerry, I saw that he was not just ahead of me, but more than five meters below me as well -- and his bubbles were going down instead of rising up. He was in a downcurrent. As I watched, Jerry made a sharp turn straight out to sea and kicked hard into the blue. The maneuver worked and he escaped the downdraft, and circled back to the wall. We backtracked in the direction we'd come from rather than risk being pushed deeper again.

Some currents are more a nuisance than anything. We recently unearthed a certain batch of photos I had taken in the Red Sea, and had a good laugh recalling what it took to get the shots. It was during a shallow night dive in a sandy area with a lot of patch reefs -- an area we knew to be particularly rich in little critters of the sort that only emerge from their lairs after dark, so I set up my camera for macro photography. When we entered the water we noticed that there was a current that we hadn't expected, but since we had planned a shallow dive close to the boat, we continued.

We shined our lights around on the sand, and sure enough there were all kinds of interesting photo subjects, especially tiny things. That was the good news. The bad news was that the current sweeping across the sand grew in intensity over the course of the dive.

We shined our lights around on the sand, and sure enough there were all kinds of interesting photo subjects, especially tiny things. That was the good news. The bad news was that the current sweeping across the sand grew in intensity over the course of the dive.

I spent most of that dive on my belly in the sand, sort of slithering along from one tiny subject to the next. As the current picked up, it wanted to flip me over, so Jerry spent most of the dive lying crosswise across my legs to hold me in place while I operated the camera. I'm sure that if anyone chanced upon us we would have made a really peculiar sight, and who knows what they would have thought we were doing! Really folks, it was just teamwork.

The picture at right is one result of our teamwork that night. You might have to click on the photo to enlarge it in order to see the teeny-tiny nearly transparent crab hiding at the base of the larger creature (called a sea pen - a relative of anemones).

Then there are the terror currents -- the ones that are not only unexpected, but so sudden and strong that they can sweep a diver away. The worst experience we ever had with one of those was at the Brothers Islands in the Red Sea, an area known for strong currents. The current we encountered there one July afternoon challenged us to the maximum.

Our boat had dropped all of the divers in our party along the fringe reef of Little Brother, the smaller of the two islands. The boat then continued to a mooring at the very tip of the island. The plan was for a one-way dive, meandering along the reef to where it ended, at the tip. It was one of those dreamy dives where everything was perfect -- the light was good, the visibility was excellent, the lush reef was spectacular, and there was no current.

Jerry and I were the lead pair of divers. The others were strung out behind us in twos and threes in a parade along the reef. At last we came to the tip of the island. Our boat and another were moored there. The other boat, let's call it #2, was moored close to the reef, having arrived there first, so ours was tied up at the mooring a bit offshore. We surfaced, identified our boat, and began to swim toward the boarding ladder at its stern.

As soon as we left the lee of the island we felt the current. We were swimming with our faces in the water, and just as we felt the current we spotted our boat's mooring line, stretched taught and actually vibrating in the current. We could see the bottom of the boarding ladder just below the surface, and underneath it the boat's propellers. The propellers were whirling as if the boat were underway, even though the engines were completely shut down, another indication of a rather strong current.

We barely had time to consider what we were seeing, because suddenly we felt like we were swimming upstream. The closer we got to the boat -- and the farther away from land -- the stronger the current. In less than a minute, we were making no headway at all.

We had begun our surface swim side by side, but since I had the bulky camera rig to push along I began to lose ground. I felt myself really beginning to huff and puff with exertion -- not a good sign. We were now less than 3 meters from the boarding ladder, but just couldn't make any headway at all, even though we are both strong swimmers. It was the most frustrating feeling.

Jerry made a few inordinately strong kicks and finally pulled ahead of me. A few more kicks like that and I saw his hand reach out and touch the ladder just as I ran out of steam and began to be swept backwards by the current.

It's funny how, in times like that, all of the training you've had clicks in and behavior switches to automatic. Realizing in a flash that I was not going to make it to the boat and that I was being swept away, I quit fighting the current, deflated my dive vest and dived under the surface. I let the current carry me nearer to boat #2, and I managed to dive deep enough to swim under the vessel. I surfaced again between that boat and the shore, again in the lee where there was no current.

I still had to solve the problem of how to get back to our boat, but at least I was no longer being swept out to sea. I called out and some of the crew of boat #2 looked over the side. I waved my arm. They waved back and hollered hello, thinking, I guess, that I was just being friendly. I called out again, and when a face appeared at the rail, this time I yelled "I need help." This time they listened while I told them about the current, and that I needed to get to our boat.

Meanwhile, Jerry had made it aboard our boat. The crew were below having lunch, and were unaware of what was happening until Jerry came aboard, breathless. His plan was to get out of his heavy gear, and re-enter the water to swim to me with a line that was tied to the boat at one end. The only trouble with that plan was that by the time he climbed on board and looked back, I was gone. He hadn't seen me duck under the surface, and he had no idea that I had managed to dive under the other boat and had made it to the lee side.

Then everything began to happen at once. The crew of boat #2 finally understood my plight. They threw me a line, and literally hauled me alongside and around their bow. They hailed our boat and heaved a line to the crew, ultimately attaching me to that line so that the crew could haul me across.

While that was happening, the next sets of divers in our party surfaced and started to swim toward our boat -- right into the current, of course, and they were as surprised by it as we had been. Jerry and the crew of our boat rushed to set a long 'current line' -- a strong line fastened to the boat's stern at one end, with a float at the other. One by one, the returning divers now swam to the current line, and one by one they got hauled to the boarding ladder.

The current line should have been set as soon as the boat tied up at the mooring. Why it was not was never explained to us. Nevertheless we all made it, camera gear and all. In order to use his arms to swim against the current, one of the divers did have to drop his camera. Fortunately it was attached to him with a lanyard, so he didn't lose it.

Speaking of cameras, when Jerry tells his version of this story, he likes to wait until someone asks what he was thinking when he turned around after boarding the boat and realized I was gone. He always answers, "I was just hoping she hadn't dropped that expensive camera!"

One kind of current we don't like to encounter while diving is the downcurrent. Divers need to be in control of their position in the water column, and there are few things more disconcerting than to suddenly feel yourself being pushed down unexpectedly by a mass of water.

We ran into this situation one time while diving off West Caicos, in the Turks and Caicos Islands. Most of the dives in the area are 'wall dives' -- that is, along the face of cliff-like dropoffs. In this case, the top of the dropoff begins at a depth of about 20 meters, and the base of the dropoff is something like 1,000 meters straight down.

We ran into this situation one time while diving off West Caicos, in the Turks and Caicos Islands. Most of the dives in the area are 'wall dives' -- that is, along the face of cliff-like dropoffs. In this case, the top of the dropoff begins at a depth of about 20 meters, and the base of the dropoff is something like 1,000 meters straight down.The walls there are glorious -- completely encrusted with fans, sea whips, and large sponges of many colors. The wall is the underwater edge of the land, and there's nothing beyond but the open water -- deep and inky blue.

It's quite common to encounter large sharks, rays, and other pelagic fish during wall dives, which is a big part of why wall dives are so appealing. On the other hand, since there is no bottom to land on, or even to use as a reference point, buoyancy control is important. (And, I might add, you definitely don't want to drop anything!)

On this occasion, we were drifting along the wall nearly 30 meters under the surface. We were nearing what had been planned as the deepest point of our dive, so we were carefully minding our instruments for air consumption and depth. We noticed that just ahead there were clumps of bushy sea whips that were fluttering downward. I mean not just hanging downward, but fluttering as if water was being poured over them from above. (See photo.)

I paused to take a photo, and Jerry continued along ahead of me. When I looked away from the camera viewfinder and back at Jerry, I saw that he was not just ahead of me, but more than five meters below me as well -- and his bubbles were going down instead of rising up. He was in a downcurrent. As I watched, Jerry made a sharp turn straight out to sea and kicked hard into the blue. The maneuver worked and he escaped the downdraft, and circled back to the wall. We backtracked in the direction we'd come from rather than risk being pushed deeper again.

Some currents are more a nuisance than anything. We recently unearthed a certain batch of photos I had taken in the Red Sea, and had a good laugh recalling what it took to get the shots. It was during a shallow night dive in a sandy area with a lot of patch reefs -- an area we knew to be particularly rich in little critters of the sort that only emerge from their lairs after dark, so I set up my camera for macro photography. When we entered the water we noticed that there was a current that we hadn't expected, but since we had planned a shallow dive close to the boat, we continued.

We shined our lights around on the sand, and sure enough there were all kinds of interesting photo subjects, especially tiny things. That was the good news. The bad news was that the current sweeping across the sand grew in intensity over the course of the dive.

We shined our lights around on the sand, and sure enough there were all kinds of interesting photo subjects, especially tiny things. That was the good news. The bad news was that the current sweeping across the sand grew in intensity over the course of the dive.I spent most of that dive on my belly in the sand, sort of slithering along from one tiny subject to the next. As the current picked up, it wanted to flip me over, so Jerry spent most of the dive lying crosswise across my legs to hold me in place while I operated the camera. I'm sure that if anyone chanced upon us we would have made a really peculiar sight, and who knows what they would have thought we were doing! Really folks, it was just teamwork.

The picture at right is one result of our teamwork that night. You might have to click on the photo to enlarge it in order to see the teeny-tiny nearly transparent crab hiding at the base of the larger creature (called a sea pen - a relative of anemones).

Then there are the terror currents -- the ones that are not only unexpected, but so sudden and strong that they can sweep a diver away. The worst experience we ever had with one of those was at the Brothers Islands in the Red Sea, an area known for strong currents. The current we encountered there one July afternoon challenged us to the maximum.

Our boat had dropped all of the divers in our party along the fringe reef of Little Brother, the smaller of the two islands. The boat then continued to a mooring at the very tip of the island. The plan was for a one-way dive, meandering along the reef to where it ended, at the tip. It was one of those dreamy dives where everything was perfect -- the light was good, the visibility was excellent, the lush reef was spectacular, and there was no current.

Jerry and I were the lead pair of divers. The others were strung out behind us in twos and threes in a parade along the reef. At last we came to the tip of the island. Our boat and another were moored there. The other boat, let's call it #2, was moored close to the reef, having arrived there first, so ours was tied up at the mooring a bit offshore. We surfaced, identified our boat, and began to swim toward the boarding ladder at its stern.

As soon as we left the lee of the island we felt the current. We were swimming with our faces in the water, and just as we felt the current we spotted our boat's mooring line, stretched taught and actually vibrating in the current. We could see the bottom of the boarding ladder just below the surface, and underneath it the boat's propellers. The propellers were whirling as if the boat were underway, even though the engines were completely shut down, another indication of a rather strong current.

We barely had time to consider what we were seeing, because suddenly we felt like we were swimming upstream. The closer we got to the boat -- and the farther away from land -- the stronger the current. In less than a minute, we were making no headway at all.

We had begun our surface swim side by side, but since I had the bulky camera rig to push along I began to lose ground. I felt myself really beginning to huff and puff with exertion -- not a good sign. We were now less than 3 meters from the boarding ladder, but just couldn't make any headway at all, even though we are both strong swimmers. It was the most frustrating feeling.

Jerry made a few inordinately strong kicks and finally pulled ahead of me. A few more kicks like that and I saw his hand reach out and touch the ladder just as I ran out of steam and began to be swept backwards by the current.

It's funny how, in times like that, all of the training you've had clicks in and behavior switches to automatic. Realizing in a flash that I was not going to make it to the boat and that I was being swept away, I quit fighting the current, deflated my dive vest and dived under the surface. I let the current carry me nearer to boat #2, and I managed to dive deep enough to swim under the vessel. I surfaced again between that boat and the shore, again in the lee where there was no current.

I still had to solve the problem of how to get back to our boat, but at least I was no longer being swept out to sea. I called out and some of the crew of boat #2 looked over the side. I waved my arm. They waved back and hollered hello, thinking, I guess, that I was just being friendly. I called out again, and when a face appeared at the rail, this time I yelled "I need help." This time they listened while I told them about the current, and that I needed to get to our boat.

Meanwhile, Jerry had made it aboard our boat. The crew were below having lunch, and were unaware of what was happening until Jerry came aboard, breathless. His plan was to get out of his heavy gear, and re-enter the water to swim to me with a line that was tied to the boat at one end. The only trouble with that plan was that by the time he climbed on board and looked back, I was gone. He hadn't seen me duck under the surface, and he had no idea that I had managed to dive under the other boat and had made it to the lee side.

Then everything began to happen at once. The crew of boat #2 finally understood my plight. They threw me a line, and literally hauled me alongside and around their bow. They hailed our boat and heaved a line to the crew, ultimately attaching me to that line so that the crew could haul me across.

While that was happening, the next sets of divers in our party surfaced and started to swim toward our boat -- right into the current, of course, and they were as surprised by it as we had been. Jerry and the crew of our boat rushed to set a long 'current line' -- a strong line fastened to the boat's stern at one end, with a float at the other. One by one, the returning divers now swam to the current line, and one by one they got hauled to the boarding ladder.

The current line should have been set as soon as the boat tied up at the mooring. Why it was not was never explained to us. Nevertheless we all made it, camera gear and all. In order to use his arms to swim against the current, one of the divers did have to drop his camera. Fortunately it was attached to him with a lanyard, so he didn't lose it.

Speaking of cameras, when Jerry tells his version of this story, he likes to wait until someone asks what he was thinking when he turned around after boarding the boat and realized I was gone. He always answers, "I was just hoping she hadn't dropped that expensive camera!"

Current events, Part 2: Drift dives and thrill rides

In the previous post, I talked about the kinds of currents that divers encounter in the ocean. I ended with the statement that some currents are gentle, while others rip along with incredible force. Some of our most memorable dives have been in currents. Allow me to reminisce about some of the those.

After logging several thousand dives over a period of decades, as we have, you would think all those dives would blur together in memory. Indeed, some do -- yet many individual dives stand out clearly in our minds, almost as if we had done them yesterday.

Memorability often hinges on having seen something unusual or special -- a rare species, for example, or a first encounter with a big animal like a whale or a large shark. Memorability also is sealed by emotions felt during a dive, especially emotions that are fueled by an adrenalin surge.

Diving in currents often takes the form of a planned 'drift dive.' Divers enter into a known current, and ride it downstream. This is a very pleasant way to do some underwater sightseeing, because you can cover more territory with less effort. It's a lot fun -- as long as you have an exit point picked out downstream, or have a boat following your bubbles, ready to pick you up when you surface.

Diving in currents often takes the form of a planned 'drift dive.' Divers enter into a known current, and ride it downstream. This is a very pleasant way to do some underwater sightseeing, because you can cover more territory with less effort. It's a lot fun -- as long as you have an exit point picked out downstream, or have a boat following your bubbles, ready to pick you up when you surface.

Drift diving in a mild current requires that divers still swim a bit, albeit with gentle assistance from the current. In a strong current, however, swimming is unnecessary. Instead the diver focuses on steering, mostly by using his fins as a combination rudder and dive plane. That's what Jerry is doing in the photo on this page.

If you look carefully at the photo, you'll notice that Jerry's bubbles are leading him (along with a trio of friendly jacks). The bubbles are being pushed ahead by a strong current that is also propelling Jerry, excusing him from having to kick.

The strongest current we have ever ridden as a planned drift dive was in a channel along the western edge of Bunaken, a small island off North Sulawesi, Indonesia. There, a drift dive in a very swift current became a high speed thrill ride. The current was so strong that we had to assume an unusual posture, just to keep from tumbling. Instead of facing down-current in a prone position, using fins for steering (as in the photo), we had to ride along sideways in an upright position, arms folded across the chest, with our legs straight down and crossed at the ankles, using our fins as a sort of keel for stability. We whizzed along so fast that taking photos was out of the question, but it sure was one heck of an exhilarating ride. We surfaced next to our chase boat whooping and cheering and high-fiving each other.

Currents sometimes run in layers. For example, an outgoing tide may create a current heading seaward, yet if there is a strong onshore wind, it may create a layer of surface current heading toward shore. Throw some underwater topography into the mix and even stranger things can happen.

One of the craziest dives we ever did involved multiple currents in multiple layers. When I say it was a crazy dive, I mean crazy in every sense of the word. The conditions sure were crazy, and maybe we were a little crazy for doing the dive, too, but I must admit we executed it just about perfectly. Let me see if I can explain.

We were on a live-aboard dive boat in the Red Sea, visiting dive sites near the the Sinai peninsula. Aboard the vessel were a small handful of relatively new divers, and another group of five very experienced divers with advanced training who were old hands at Red Sea diving. We were a part of the latter group. Because we were already very familiar with the dive sites there, and because we were all divemasters or instructors in our own right, we were left alone to manage our own dives, freeing the boat's lone dive guide to tend to the newbies.

Late one afternoon the boat brought us to Ras Mohammed, at the tip of the Sinai peninsula. Ras Mohammed is actually a complex of dive sites. The best known sites are just off the cape at the tip of the land peninsula, where a large pinnacle rises from the sea floor hundreds of meters down. At a depth of about 25 meters, the pinnacle splits into two, with a sort of plateau running between the pinnacles and then toward the land. The eastern pinnacle is known as Shark Reef, and the western one is called Jolanda Reef. Can you picture that layout?

As the boat approached Ras Mohammed, the two groups planned their respective dives. Expecting a bit of current running westward over the plateau, the dive guide planned to lead the 'baby divers' (as they were always called) along the eastern edge of the plateau to a site known as Anemone City. Our advanced group decided to enter the water at the same spot, but to drift with the current over the plateau, then swim between the two pinnacles and around the seaward side of Jolanda Reef, the more distant of the two pinnacles from our entry point.

We arranged for Armando, the boat's Italian deckhand, to pick us up in the boat's tender at a mooring buoy on the far side of Jolanda Reef exactly 50 minutes after we entered the water. Being a safety conscious lot, we even reviewed an alternative plan with the boat's crew, in case something should go wrong. We were all equipped with 'safety sausages' -- bright orange tubes (flattened, rolled up, and carried in our pockets) that turn into 6-foot high marker buoys when inflated at the surface. We showed them to the crew, telling them that if we could not make our rendezvous point for any reason, we would surface and inflate these markers, and wait for pick-up.

Our group entered the water first, followed by the baby divers and the guide. We immediately noticed that there was a surface current running in the opposite direction from what we had expected. The divers in our group signaled to one another to descend, and sure enough the current was running in the expected direction a few meters down. We pressed on.

By the time we got to the spot between the two pinnacles where we needed to make our turn to go around the seaward side of Jolanda the current was raging, but at least it was going in the right direction. Sort of. Because the current split at the pinnacle, the current was actually pulling toward the open sea at the side where we intended to pass. We needed to hug close to the pinnacle in order to round it, and we had to kick with all our might for a minute or two just to steer through the turbulence. Once we rounded the corner we had a free ride with the current again pushing us along effortlessly.

All of this took twenty minutes. We now had a half hour to kill before our pick-up. We poked along, back and forth across the face of the pinnacle, taking in the scenery and peeking into holes and on ledges as we ascended very, very gradually. As we approached 10 meters of depth, we encountered another current that pushed us seaward. We swam out of it in an arc, back toward the pinnacle, and again ended up in the pretty coral garden under the mooring buoy that was our target. Near the end of our allotted time now, we stayed there.

We heard the putter of the little outboard engine on the Zodiac as it approached. The deckhand shut off the motor and tied up to the mooring buoy just as the five of us popped our heads above the surface alongside the little rubber boat. Armando yelled as if he had seen a ghost, and blessed himself several times. As we hauled ourselves aboard, he kissed each one of us on the cheek. Clearly he was glad to see us!

Unbeknown to us, it turned out that the guide and the baby divers had aborted their dive after less than five minutes because they could not handle the surface current. The guide told the crew they had better start looking for us right away, because there was no way we would be able to make it to the mooring buoy as planned. They all had spent the past 45 minutes scanning the horizon, watching for our orange signal sausages, fearing we had been swept out to the open sea. They didn't see us, of course, because we had continued our dive as planned.

Armando had brought the Zodiac to the rendezvous point at the mooring buoy on schedule, but apparently hadn't really expected to see us. When we surfaced just when we said we would, just where we said we would, no one could believe it. When we got back to the boat everyone cheered. They treated us as if we really had been lost at sea and recovered, whereas the five of us felt we had simply "planned our dive, and dived our plan." Only in hindsight did we start to believe that maybe we had been a little crazy to continue in those crazy conditions.

Next time: A final episode on currents (at least for now).

After logging several thousand dives over a period of decades, as we have, you would think all those dives would blur together in memory. Indeed, some do -- yet many individual dives stand out clearly in our minds, almost as if we had done them yesterday.

Memorability often hinges on having seen something unusual or special -- a rare species, for example, or a first encounter with a big animal like a whale or a large shark. Memorability also is sealed by emotions felt during a dive, especially emotions that are fueled by an adrenalin surge.

Diving in currents often takes the form of a planned 'drift dive.' Divers enter into a known current, and ride it downstream. This is a very pleasant way to do some underwater sightseeing, because you can cover more territory with less effort. It's a lot fun -- as long as you have an exit point picked out downstream, or have a boat following your bubbles, ready to pick you up when you surface.

Diving in currents often takes the form of a planned 'drift dive.' Divers enter into a known current, and ride it downstream. This is a very pleasant way to do some underwater sightseeing, because you can cover more territory with less effort. It's a lot fun -- as long as you have an exit point picked out downstream, or have a boat following your bubbles, ready to pick you up when you surface.Drift diving in a mild current requires that divers still swim a bit, albeit with gentle assistance from the current. In a strong current, however, swimming is unnecessary. Instead the diver focuses on steering, mostly by using his fins as a combination rudder and dive plane. That's what Jerry is doing in the photo on this page.

If you look carefully at the photo, you'll notice that Jerry's bubbles are leading him (along with a trio of friendly jacks). The bubbles are being pushed ahead by a strong current that is also propelling Jerry, excusing him from having to kick.

The strongest current we have ever ridden as a planned drift dive was in a channel along the western edge of Bunaken, a small island off North Sulawesi, Indonesia. There, a drift dive in a very swift current became a high speed thrill ride. The current was so strong that we had to assume an unusual posture, just to keep from tumbling. Instead of facing down-current in a prone position, using fins for steering (as in the photo), we had to ride along sideways in an upright position, arms folded across the chest, with our legs straight down and crossed at the ankles, using our fins as a sort of keel for stability. We whizzed along so fast that taking photos was out of the question, but it sure was one heck of an exhilarating ride. We surfaced next to our chase boat whooping and cheering and high-fiving each other.

Currents sometimes run in layers. For example, an outgoing tide may create a current heading seaward, yet if there is a strong onshore wind, it may create a layer of surface current heading toward shore. Throw some underwater topography into the mix and even stranger things can happen.

One of the craziest dives we ever did involved multiple currents in multiple layers. When I say it was a crazy dive, I mean crazy in every sense of the word. The conditions sure were crazy, and maybe we were a little crazy for doing the dive, too, but I must admit we executed it just about perfectly. Let me see if I can explain.

We were on a live-aboard dive boat in the Red Sea, visiting dive sites near the the Sinai peninsula. Aboard the vessel were a small handful of relatively new divers, and another group of five very experienced divers with advanced training who were old hands at Red Sea diving. We were a part of the latter group. Because we were already very familiar with the dive sites there, and because we were all divemasters or instructors in our own right, we were left alone to manage our own dives, freeing the boat's lone dive guide to tend to the newbies.

Late one afternoon the boat brought us to Ras Mohammed, at the tip of the Sinai peninsula. Ras Mohammed is actually a complex of dive sites. The best known sites are just off the cape at the tip of the land peninsula, where a large pinnacle rises from the sea floor hundreds of meters down. At a depth of about 25 meters, the pinnacle splits into two, with a sort of plateau running between the pinnacles and then toward the land. The eastern pinnacle is known as Shark Reef, and the western one is called Jolanda Reef. Can you picture that layout?

As the boat approached Ras Mohammed, the two groups planned their respective dives. Expecting a bit of current running westward over the plateau, the dive guide planned to lead the 'baby divers' (as they were always called) along the eastern edge of the plateau to a site known as Anemone City. Our advanced group decided to enter the water at the same spot, but to drift with the current over the plateau, then swim between the two pinnacles and around the seaward side of Jolanda Reef, the more distant of the two pinnacles from our entry point.

We arranged for Armando, the boat's Italian deckhand, to pick us up in the boat's tender at a mooring buoy on the far side of Jolanda Reef exactly 50 minutes after we entered the water. Being a safety conscious lot, we even reviewed an alternative plan with the boat's crew, in case something should go wrong. We were all equipped with 'safety sausages' -- bright orange tubes (flattened, rolled up, and carried in our pockets) that turn into 6-foot high marker buoys when inflated at the surface. We showed them to the crew, telling them that if we could not make our rendezvous point for any reason, we would surface and inflate these markers, and wait for pick-up.

Our group entered the water first, followed by the baby divers and the guide. We immediately noticed that there was a surface current running in the opposite direction from what we had expected. The divers in our group signaled to one another to descend, and sure enough the current was running in the expected direction a few meters down. We pressed on.

By the time we got to the spot between the two pinnacles where we needed to make our turn to go around the seaward side of Jolanda the current was raging, but at least it was going in the right direction. Sort of. Because the current split at the pinnacle, the current was actually pulling toward the open sea at the side where we intended to pass. We needed to hug close to the pinnacle in order to round it, and we had to kick with all our might for a minute or two just to steer through the turbulence. Once we rounded the corner we had a free ride with the current again pushing us along effortlessly.

All of this took twenty minutes. We now had a half hour to kill before our pick-up. We poked along, back and forth across the face of the pinnacle, taking in the scenery and peeking into holes and on ledges as we ascended very, very gradually. As we approached 10 meters of depth, we encountered another current that pushed us seaward. We swam out of it in an arc, back toward the pinnacle, and again ended up in the pretty coral garden under the mooring buoy that was our target. Near the end of our allotted time now, we stayed there.

We heard the putter of the little outboard engine on the Zodiac as it approached. The deckhand shut off the motor and tied up to the mooring buoy just as the five of us popped our heads above the surface alongside the little rubber boat. Armando yelled as if he had seen a ghost, and blessed himself several times. As we hauled ourselves aboard, he kissed each one of us on the cheek. Clearly he was glad to see us!

Unbeknown to us, it turned out that the guide and the baby divers had aborted their dive after less than five minutes because they could not handle the surface current. The guide told the crew they had better start looking for us right away, because there was no way we would be able to make it to the mooring buoy as planned. They all had spent the past 45 minutes scanning the horizon, watching for our orange signal sausages, fearing we had been swept out to the open sea. They didn't see us, of course, because we had continued our dive as planned.

Armando had brought the Zodiac to the rendezvous point at the mooring buoy on schedule, but apparently hadn't really expected to see us. When we surfaced just when we said we would, just where we said we would, no one could believe it. When we got back to the boat everyone cheered. They treated us as if we really had been lost at sea and recovered, whereas the five of us felt we had simply "planned our dive, and dived our plan." Only in hindsight did we start to believe that maybe we had been a little crazy to continue in those crazy conditions.

Next time: A final episode on currents (at least for now).

Current events: Water that moves

Take a look at the photo on this page, and tell me: If you had to give it a one-word label, what would that be?

Non-divers might think something like 'pastels.' To a diver that photo screams current! That's 'current' as in moving water. [You can click on the photo for a larger view.]

Not only are the soft corals in the photo bending like wheat in a windswept field, but all the little fishies are facing in the same direction. That's what little fishies do in a current -- they point their little noses into the current and wiggle their tails for all they are worth, just to stay in place.

Not only are the soft corals in the photo bending like wheat in a windswept field, but all the little fishies are facing in the same direction. That's what little fishies do in a current -- they point their little noses into the current and wiggle their tails for all they are worth, just to stay in place.

Good divers recognize and understand currents in the ocean, and know how to deal with them. The two most common factors relating to the kinds of currents that divers are likely to encounter are wind and tides.

Currents relatively close to the surface can be caused by wind blowing across the water. When wind blows across the surface it pushes a certain amount of water ahead of it. The stronger the wind, and the more open and unsheltered the surface, the stronger the surface current. Most wind-driven surface currents in coastal areas are only a meter or so deep -- a good thing to know. For instance, if there's a wind-driven surface current, a diver will probably have an easier time swimming back to a boat or a shoreline exit point by swimming a couple of meters beneath the surface instead of on the surface.

Some currents are caused by changing tides. The water mass flows toward shore during an incoming tide (called flood flow), and sucks back out to sea during an outgoing tide (called ebb flow).

Currents can be enhanced by underwater topography and the shape of a coastline. Think of the way water in a river or creek flows around rocks and other obstructions. The same thing happens underwater. If there is some relatively large feature in the path of the water mass during a tidal shift, for example, the water will flow around it and the current usually will be stronger and more turbulent closest to the obstruction. The same thing happens where there is a bottleneck -- a place where the flow of water gets squished between two large obstructions.

Currents encountered by divers most often move horizontally, but there are places and times where vertical currents are encountered. Upwellings occur when deeper water rises toward the surface. Downwellings occur in some places, too, but a more common type of downward current a diver may encounter happens where there is a dropoff of some sort. For example, a tidal ebb flow may literally spill over an underwater dropoff, just like a waterfall spills over a cliff on land.

Some currents are gentle, while others rip along with incredible force. Next time I'll tell you about some very interesting experiences we've had dealing with currents while diving.

Non-divers might think something like 'pastels.' To a diver that photo screams current! That's 'current' as in moving water. [You can click on the photo for a larger view.]

Not only are the soft corals in the photo bending like wheat in a windswept field, but all the little fishies are facing in the same direction. That's what little fishies do in a current -- they point their little noses into the current and wiggle their tails for all they are worth, just to stay in place.

Not only are the soft corals in the photo bending like wheat in a windswept field, but all the little fishies are facing in the same direction. That's what little fishies do in a current -- they point their little noses into the current and wiggle their tails for all they are worth, just to stay in place.Good divers recognize and understand currents in the ocean, and know how to deal with them. The two most common factors relating to the kinds of currents that divers are likely to encounter are wind and tides.

Currents relatively close to the surface can be caused by wind blowing across the water. When wind blows across the surface it pushes a certain amount of water ahead of it. The stronger the wind, and the more open and unsheltered the surface, the stronger the surface current. Most wind-driven surface currents in coastal areas are only a meter or so deep -- a good thing to know. For instance, if there's a wind-driven surface current, a diver will probably have an easier time swimming back to a boat or a shoreline exit point by swimming a couple of meters beneath the surface instead of on the surface.

Some currents are caused by changing tides. The water mass flows toward shore during an incoming tide (called flood flow), and sucks back out to sea during an outgoing tide (called ebb flow).

Currents can be enhanced by underwater topography and the shape of a coastline. Think of the way water in a river or creek flows around rocks and other obstructions. The same thing happens underwater. If there is some relatively large feature in the path of the water mass during a tidal shift, for example, the water will flow around it and the current usually will be stronger and more turbulent closest to the obstruction. The same thing happens where there is a bottleneck -- a place where the flow of water gets squished between two large obstructions.

Currents encountered by divers most often move horizontally, but there are places and times where vertical currents are encountered. Upwellings occur when deeper water rises toward the surface. Downwellings occur in some places, too, but a more common type of downward current a diver may encounter happens where there is a dropoff of some sort. For example, a tidal ebb flow may literally spill over an underwater dropoff, just like a waterfall spills over a cliff on land.

Some currents are gentle, while others rip along with incredible force. Next time I'll tell you about some very interesting experiences we've had dealing with currents while diving.

Blog Action Day: What's wrong with this picture?

Today is Blog Action Day. Thousands of bloggers around the world are uniting today to address environmental issues. As divers and ocean lovers, we have a particular concern for the marine environment. We'd like to show you a few examples of how marine debris -- from large items to small -- degrade the marine environment.

If "a picture says a thousand words," then here are 3000 words about why you should do your part to reduce marine debris:

These are only a few examples of marine debris that we have seen underwater. Most people don't think about marine debris because they can't see it. Believe us -- it's there, and most of it stays there forever to damage the marine environment by entangling wildlife and smothering reefs. Click here for tips on how you can do your part to reduce marine debris.

For more information, visit the NOAA page about marine debris.

If "a picture says a thousand words," then here are 3000 words about why you should do your part to reduce marine debris:

A discarded tire spoils a pretty reef scene.

A derelict fishing net completely smothers this reef.

Even small bits of debris can do damage.

Here a newspaper chokes a lovely soft coral.

Here a newspaper chokes a lovely soft coral.

These are only a few examples of marine debris that we have seen underwater. Most people don't think about marine debris because they can't see it. Believe us -- it's there, and most of it stays there forever to damage the marine environment by entangling wildlife and smothering reefs. Click here for tips on how you can do your part to reduce marine debris.

For more information, visit the NOAA page about marine debris.

A Right Blue thank you to our virtual friends

This blog, The Right Blue, is three months old today. The growth of this project since its launch in mid-July has greatly exceeded our expectations on every measure.

This blog, The Right Blue, is three months old today. The growth of this project since its launch in mid-July has greatly exceeded our expectations on every measure. At the time we launched The Right Blue, we imagined that the project would be of interest mainly to our family, and our old friends and dive pals. We hoped that perhaps a few other divers and photographers also might find The Right Blue and enjoy it, but we really didn't expect the reach to be very wide.

Much to our amazement and delight, The Right Blue quickly attracted many visitors beyond our circle of family and friends, and it turns out that a large percentage of those visitors return again and again. We know this not only from our traffic statistics, but because they give us feedback via comments on individual posts and on our contact form. A substantial number have subscribed to our RSS feed. They like The Right Blue!

Among those regular visitors are some fellow bloggers, none of whom we have ever met in person, and most of whom are not divers! They became virtual friends and supporters who have encouraged us and helped spread the word about our project by linking to us, submitting our posts to social bookmarking sites, and writing unsolicited reviews of The Right Blue. (Click here for a list of those who have linked to us.)

Today we'd like to acknowledge these friends who have helped make The Right Blue such a success in just three months time. In particular, we thank Brian (Apathetic Lemming of the North), Marisa (Marisa's Dandelion Patch), and Charley (Planet Kauai) for writing very kind reviews of The Right Blue in their blogs. Mike (Reality Is Over Rated) specifically praised The Right Blue in a discussion thread on Blog Catalog. Jim and Em at GO! Smell the flowers not only wrote a review of The Right Blue, but invited us to participate by replying to the many comments to their article about diving.

We thank Evelyn (Homespun Honolulu) for including a post from The Right Blue in the Blog Carnival of Aloha. Pua at the Best Hawaii Vacation Blog asked us to write a guest post about diving in Hawaii, which was published yesterday.

The members of the Photography Group at Blog Catalog also have been particularly supportive and encouraging, and Wordless Wednesday participants have visited The Right Blue in droves.

Thank you all so much. We truly appreciate your support and we hope you continue to enjoy the stories and photos of The Right Blue.

Underwater boogie

If you think that all divers do underwater is swim around and watch pretty fishies, think again. Check out this video of divers Doug Silton and Dax Hock demonstrating their underwater dancing prowess. Not everyone can do the Shim Sham and the Lindy Hop 22 meters below the surface!

(If the video does not display or play properly above, click here to watch Doug and Dax on YouTube.)

The video of Doug and Dax was shot while they were on vacation last year at Ko Tao, Thailand. Thanks so much to DougSilton for posting this terrific video on YouTube for all of us to enjoy. How about a nice round of applause for Doug and Dax!

[Tip of the hat to Craig McClain for posting the video on his blog, Deep Sea News, which is where we first saw it.]

(If the video does not display or play properly above, click here to watch Doug and Dax on YouTube.)

The video of Doug and Dax was shot while they were on vacation last year at Ko Tao, Thailand. Thanks so much to DougSilton for posting this terrific video on YouTube for all of us to enjoy. How about a nice round of applause for Doug and Dax!

[Tip of the hat to Craig McClain for posting the video on his blog, Deep Sea News, which is where we first saw it.]

Why I love macro photography : Details, details

I love macro photography. (For those of you not familiar with the terminology, 'macro photography' refers to ultra-close-up shots.)

I love macro photography. (For those of you not familiar with the terminology, 'macro photography' refers to ultra-close-up shots.)What I love most about macro photography are the surprise elements that always pop out. Those surprises are fine details that either can't be seen or aren't noticed with the naked eye, but which emerge clearly when the macro photo is enlarged.

The 1:1 macro shot of the little hermit crab on this page is a perfect example of what I'm talking about. The shell that is this little guy's home was all of an inch (about 2.5 cm) long. As I lay on my belly to photograph this subject I could see the shell, and the crab, and I could tell that the crab was a reddish color. I could make out legs and eyestalks -- but until the film was processed, I had no idea that the crab's eyes were turquoise, or that he had such hairy legs! (Click on the photo for a larger version, and you'll see what I mean.)

We don't know the species name for this hermit crab. If anyone out there does know, please tell us. It was photographed in the Mediterranean Sea at Konnos Bay, Cyprus at a depth of less than two meters.

Myrtle's special spot on the Puako reef

Puako, Hawaii is blessed with a spectacular fringe reef that runs parallel to the shoreline, but if you are beginning a dive from shore, you have to swim a bit to get to the reef. I mentioned in an earlier post that the inshore water is shallow, due to a lava shelf that extends seaward from the shoreline. That shelf ends at a precipitous dropoff. There the water depth abruptly changes from one or two meters, to about eight to ten meters. It takes most people a solid five to ten minutes of swimming to get to the dropoff, but it's worth the effort.

The underwater terrain along the seaward face of the dropoff is dramatic. There are cavelets and tunnels and arches formed by the ancient lava flow, all of which are now covered with coral and other marine growth, and inhabited by a multitude of fish and little creatures.

The underwater terrain along the seaward face of the dropoff is dramatic. There are cavelets and tunnels and arches formed by the ancient lava flow, all of which are now covered with coral and other marine growth, and inhabited by a multitude of fish and little creatures.

Beginning at the base of the dropoff and extending seaward is a vast coral garden, composed mostly of a species of finger coral (Porites compressa), with other hard corals in patches here and there. These acres and acres of coral form the main fringe reef that parallels the entire coast of Puako and beyond.

This area is densely populated with abundant marine life of all kinds: Virtually every type of fish or reef creature known to live in Hawaiian waters can be found somewhere along Puako's reef.

The green sea turtles in Puako spend a good bit of their time feeding in the shallows, or basking on the edge of the shore. They also spend a part of each day on the reef. The terrain on the reef is nearly level in some areas, gently sloping in others. There are holes and ledges here and there, and some of those are turtle hideouts.

The turtles near the shoreline favor a particular area for grazing and sunning themselves. Once you are able to recognize an individual turtle you will be able to reliably find that turtle in the same area, day after day. This certainly was the case for the turtle we named Myrtle.

From the time we first came to know her, we would occasionally cross paths with Myrtle near the dropoff. Usually we would pass her swimming in the opposite direction -- either she'd be heading in to shore when we were headed out for a dive, or she'd be approaching the dropoff just as we were ascending at the end of our dive. We always wondered where she went on the reef, but it was a long time before we encountered her beyond the dropoff.

From the time we first came to know her, we would occasionally cross paths with Myrtle near the dropoff. Usually we would pass her swimming in the opposite direction -- either she'd be heading in to shore when we were headed out for a dive, or she'd be approaching the dropoff just as we were ascending at the end of our dive. We always wondered where she went on the reef, but it was a long time before we encountered her beyond the dropoff.

Finally we spotted her one day, swimming over the coral garden. As soon as we were sure it really was Myrtle, we signaled to each other to follow her. We were so curious to see where she would go.

She seemed very unconcerned to have us swimming alongside her. She stayed her course and neither sped up nor slowed her pace. After a few minutes we approached a rather large hump in the coral. Myrtle ceased paddling with her flippers. She glided toward the coral formation and plopped down near its base. She landed a bit clumsily, then turned around and snuggled her turtle butt into a depression in the coral. There she rested.

We watched her there for a few minutes. She looked a bit like an old lady sitting on her porch, watching the world go by. She looked our way a few times, but seemed quite settled, so we swam off.

We watched her there for a few minutes. She looked a bit like an old lady sitting on her porch, watching the world go by. She looked our way a few times, but seemed quite settled, so we swam off.

About an hour later as we were headed back across the reef toward the dropoff for our ascent, we chose our route to pass by the same lumpy coral formation. We checked the hole where we last saw Myrtle. Myrtle was gone.

But then, guess who we saw as we waded ashore: Myrtle, of course, back in her favorite cove, grazing on limu as usual. And now that we knew the location of Myrtle's secret spot on the reef, we knew just where to look for her when she wasn't in the shallows or on the beach.

The underwater terrain along the seaward face of the dropoff is dramatic. There are cavelets and tunnels and arches formed by the ancient lava flow, all of which are now covered with coral and other marine growth, and inhabited by a multitude of fish and little creatures.

The underwater terrain along the seaward face of the dropoff is dramatic. There are cavelets and tunnels and arches formed by the ancient lava flow, all of which are now covered with coral and other marine growth, and inhabited by a multitude of fish and little creatures.Beginning at the base of the dropoff and extending seaward is a vast coral garden, composed mostly of a species of finger coral (Porites compressa), with other hard corals in patches here and there. These acres and acres of coral form the main fringe reef that parallels the entire coast of Puako and beyond.

This area is densely populated with abundant marine life of all kinds: Virtually every type of fish or reef creature known to live in Hawaiian waters can be found somewhere along Puako's reef.

The green sea turtles in Puako spend a good bit of their time feeding in the shallows, or basking on the edge of the shore. They also spend a part of each day on the reef. The terrain on the reef is nearly level in some areas, gently sloping in others. There are holes and ledges here and there, and some of those are turtle hideouts.

The turtles near the shoreline favor a particular area for grazing and sunning themselves. Once you are able to recognize an individual turtle you will be able to reliably find that turtle in the same area, day after day. This certainly was the case for the turtle we named Myrtle.

From the time we first came to know her, we would occasionally cross paths with Myrtle near the dropoff. Usually we would pass her swimming in the opposite direction -- either she'd be heading in to shore when we were headed out for a dive, or she'd be approaching the dropoff just as we were ascending at the end of our dive. We always wondered where she went on the reef, but it was a long time before we encountered her beyond the dropoff.

From the time we first came to know her, we would occasionally cross paths with Myrtle near the dropoff. Usually we would pass her swimming in the opposite direction -- either she'd be heading in to shore when we were headed out for a dive, or she'd be approaching the dropoff just as we were ascending at the end of our dive. We always wondered where she went on the reef, but it was a long time before we encountered her beyond the dropoff.Finally we spotted her one day, swimming over the coral garden. As soon as we were sure it really was Myrtle, we signaled to each other to follow her. We were so curious to see where she would go.

She seemed very unconcerned to have us swimming alongside her. She stayed her course and neither sped up nor slowed her pace. After a few minutes we approached a rather large hump in the coral. Myrtle ceased paddling with her flippers. She glided toward the coral formation and plopped down near its base. She landed a bit clumsily, then turned around and snuggled her turtle butt into a depression in the coral. There she rested.

We watched her there for a few minutes. She looked a bit like an old lady sitting on her porch, watching the world go by. She looked our way a few times, but seemed quite settled, so we swam off.

We watched her there for a few minutes. She looked a bit like an old lady sitting on her porch, watching the world go by. She looked our way a few times, but seemed quite settled, so we swam off.About an hour later as we were headed back across the reef toward the dropoff for our ascent, we chose our route to pass by the same lumpy coral formation. We checked the hole where we last saw Myrtle. Myrtle was gone.

But then, guess who we saw as we waded ashore: Myrtle, of course, back in her favorite cove, grazing on limu as usual. And now that we knew the location of Myrtle's secret spot on the reef, we knew just where to look for her when she wasn't in the shallows or on the beach.

Meet Myrtle the turtle

As I explained earlier, many green sea turtles live along the shoreline at Puako, Hawaii. They cruise around the reef, graze on algae and seaweed in the shallows, and sunbathe on the rocks and beaches there. We'd like to introduce you to one of those turtles.

This is Myrtle, a Hawaiian green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas). Over a period of several years, we got to know Myrtle quite well. Because we got to know Myrtle, we learned a lot about green sea turtles and how they live.

This is Myrtle, a Hawaiian green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas). Over a period of several years, we got to know Myrtle quite well. Because we got to know Myrtle, we learned a lot about green sea turtles and how they live.

Myrtle's base of operations in Puako happened to be the particular little cove where we most often enter the water to begin our shore dives. While quite a few turtles hang out in that area, we noticed that one particular turtle had a small 'ding' right in the center of her carapace. That little blemish in her shell set her apart from the others and made her easy to identify. We named her Myrtle -- not the most original name for a turtle, I know, but it suited her. (Take a look at that face in the photo and tell me she doesn't look like a Myrtle!)

At the time we first encountered Myrtle, Jerry and I were living in Puako, right across the street from the little cove where this turtle lived. Our good friend Dan lived just up the road. During the time that we all lived there, Dan and Jerry and I visited the cove on a daily basis, whether we were diving or not. It was during this period that this spot became our favorite, and that we got to know Myrtle.

Once we learned to recognize Myrtle, we noticed that she was there almost all the time. So, one of the first things we learned from Myrtle is that green sea turtles are creatures of habit.

Sometimes we'd see her basking on the beach, 'working on her tan.' Most often we'd see Myrtle in the water close to shore, munching away on the limu (seaweed) that covers the rocks there in the shallows, just as she's doing in the photo at right. Occasionally we'd cross paths with her while diving out on the reef beyond the dropoff. More on that later...

Sometimes we'd see her basking on the beach, 'working on her tan.' Most often we'd see Myrtle in the water close to shore, munching away on the limu (seaweed) that covers the rocks there in the shallows, just as she's doing in the photo at right. Occasionally we'd cross paths with her while diving out on the reef beyond the dropoff. More on that later...

Most of the sea turtles around Puako are quite laid back, especially when they're basking on the rocks or the beach. By this I mean that they are not very skittish in the presence of people -- almost as if they know they are protected by law, and that no human will harm them. (Either that, or the warm sun just makes them drowsy!)

The sea turtles in Puako can be a little touchy about having their space invaded when they are feeding, however. If waders approach them, they'll often pointedly shove off from the bottom and swim at least a few meters away. We'd see Myrtle do that, too, but then we noticed something interesting.

As I mentioned, we had almost daily encounters with Myrtle for years. We began to notice that if we waded past Myrtle while wearing our wetsuits and dive boots, she never spooked. Perhaps she grew accustomed to seeing us -- or rather our neoprene-clad legs and feet! -- and understood that the humans attached to those legs and feet were not going to harass her. That thought was reinforced by the fact that if we waded into the water bare-legged, bam! Myrtle would take off.

There is a sound reason why sea turtles tend to stay clear of anything unfamiliar, including people, while they are underwater. Sea turtles can stay underwater for a considerable length of time, but they are air breathers. They need to surface from time to time for a breath, so they have an innate fear of being cornered or restrained underwater.

Nevertheless, Myrtle often would pop her head above the surface and look right at us as we waded past her -- as long as we were decked out in our dive gear. We used to ask one another if we were imagining that she recognized us (or our neoprene), and of course we can't say for sure, but it did seem more than a coincidence that just as we'd pass by her, she'd interrupt her grazing and pop up as if to say hello.

As if! What she really did was exhale her turtle breath in our direction, and then she'd duck her head back under the water to take another pass at the limu buffet below. We'd do our dive, and an hour or so later when we waded back to shore, Myrtle would still be there. Once more she'd surface as we waded past, and give us another big whiff of limu breath.

We have lots of Myrtle stories. Next time, I'll tell you a bit more about this special turtle and what we learned from her.

This is Myrtle, a Hawaiian green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas). Over a period of several years, we got to know Myrtle quite well. Because we got to know Myrtle, we learned a lot about green sea turtles and how they live.

This is Myrtle, a Hawaiian green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas). Over a period of several years, we got to know Myrtle quite well. Because we got to know Myrtle, we learned a lot about green sea turtles and how they live.Myrtle's base of operations in Puako happened to be the particular little cove where we most often enter the water to begin our shore dives. While quite a few turtles hang out in that area, we noticed that one particular turtle had a small 'ding' right in the center of her carapace. That little blemish in her shell set her apart from the others and made her easy to identify. We named her Myrtle -- not the most original name for a turtle, I know, but it suited her. (Take a look at that face in the photo and tell me she doesn't look like a Myrtle!)

At the time we first encountered Myrtle, Jerry and I were living in Puako, right across the street from the little cove where this turtle lived. Our good friend Dan lived just up the road. During the time that we all lived there, Dan and Jerry and I visited the cove on a daily basis, whether we were diving or not. It was during this period that this spot became our favorite, and that we got to know Myrtle.

Once we learned to recognize Myrtle, we noticed that she was there almost all the time. So, one of the first things we learned from Myrtle is that green sea turtles are creatures of habit.

Sometimes we'd see her basking on the beach, 'working on her tan.' Most often we'd see Myrtle in the water close to shore, munching away on the limu (seaweed) that covers the rocks there in the shallows, just as she's doing in the photo at right. Occasionally we'd cross paths with her while diving out on the reef beyond the dropoff. More on that later...

Sometimes we'd see her basking on the beach, 'working on her tan.' Most often we'd see Myrtle in the water close to shore, munching away on the limu (seaweed) that covers the rocks there in the shallows, just as she's doing in the photo at right. Occasionally we'd cross paths with her while diving out on the reef beyond the dropoff. More on that later...Most of the sea turtles around Puako are quite laid back, especially when they're basking on the rocks or the beach. By this I mean that they are not very skittish in the presence of people -- almost as if they know they are protected by law, and that no human will harm them. (Either that, or the warm sun just makes them drowsy!)

The sea turtles in Puako can be a little touchy about having their space invaded when they are feeding, however. If waders approach them, they'll often pointedly shove off from the bottom and swim at least a few meters away. We'd see Myrtle do that, too, but then we noticed something interesting.

As I mentioned, we had almost daily encounters with Myrtle for years. We began to notice that if we waded past Myrtle while wearing our wetsuits and dive boots, she never spooked. Perhaps she grew accustomed to seeing us -- or rather our neoprene-clad legs and feet! -- and understood that the humans attached to those legs and feet were not going to harass her. That thought was reinforced by the fact that if we waded into the water bare-legged, bam! Myrtle would take off.

There is a sound reason why sea turtles tend to stay clear of anything unfamiliar, including people, while they are underwater. Sea turtles can stay underwater for a considerable length of time, but they are air breathers. They need to surface from time to time for a breath, so they have an innate fear of being cornered or restrained underwater.

Nevertheless, Myrtle often would pop her head above the surface and look right at us as we waded past her -- as long as we were decked out in our dive gear. We used to ask one another if we were imagining that she recognized us (or our neoprene), and of course we can't say for sure, but it did seem more than a coincidence that just as we'd pass by her, she'd interrupt her grazing and pop up as if to say hello.

As if! What she really did was exhale her turtle breath in our direction, and then she'd duck her head back under the water to take another pass at the limu buffet below. We'd do our dive, and an hour or so later when we waded back to shore, Myrtle would still be there. Once more she'd surface as we waded past, and give us another big whiff of limu breath.

We have lots of Myrtle stories. Next time, I'll tell you a bit more about this special turtle and what we learned from her.

Diving at Puako: There's no place like home

Last week we began to tell our readers about Puako, Hawaii -- the place we consider to be our home base, as divers. Puako has a magnificently rugged shoreline formed by an old lava flow. There are a few small sandy beaches there, but most of the shoreline is rocky and very irregular.

Last week we began to tell our readers about Puako, Hawaii -- the place we consider to be our home base, as divers. Puako has a magnificently rugged shoreline formed by an old lava flow. There are a few small sandy beaches there, but most of the shoreline is rocky and very irregular.It makes a pretty picture, of course, but it is what's offshore under the water that draws us back there again and again. The photo at right shows our favorite entry point for shore diving at Puako.

We have waded into the ocean hundreds of times at this very spot to begin a dive. In fact, we have dived along this section of Puako's coast so frequently that we have come to know the terrain there as well as we know our own back yard on land.

We know where all of the resident critters live along that stretch of the coast, and we gave names to many of the 'regulars.' We've drawn maps of the reef there. We know every landmark and topographical feature, and we named those, too. In fact, we know the area so intimately that we like to say that if someone so much as turned over a rock, we'd notice!