What: Macro image of a Brain Coral (Diploria strigosa)

Where: I took this photo at Angelfish Reef, Grand Cayman.

Where: I took this photo at Angelfish Reef, Grand Cayman.

BNSullivan.jpg)

[Click on the photo to enlarge.]

When we approached the first zip line, a 170-foot “bunny” line, I got butterflies in my stomach and that internal chicken was obnoxiously loud. Our guides did a great job of giving us safety pointers and telling us what to expect. So, with excited reluctance, I climbed to the platform, allowed John to hook my harness to the line. I watched him pull on the harnesses and double check the connection for safety. I asked again what I needed to do and John kindly explained it all to me again. I said a prayer, took a deep breath, and ran off the platform. It was fun and I survived.Sheila's husband took his video camera along on his zip line ride, filming a blur of foliage during the short, fast trip -- accompanied by a clearly audible yell that is part Tarzan, and part terror.

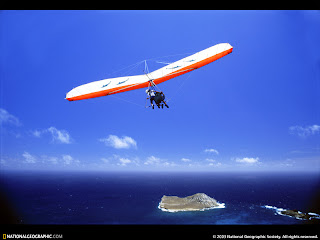

This exchange reminded Jerry and me of an experience we had years ago, when we were still living on Oahu. One day we gathered up our dive gear and went to an area near the eastern tip of the island to dive. We entered the water from an area near Makapu'u Beach, right across the road from Sea Life Park.

This exchange reminded Jerry and me of an experience we had years ago, when we were still living on Oahu. One day we gathered up our dive gear and went to an area near the eastern tip of the island to dive. We entered the water from an area near Makapu'u Beach, right across the road from Sea Life Park.BNSullivan.jpg) This funny looking little guy is a frogfish. More precisely, this species is Commerson's Frogfish (Antennarius commerson). Although there are a number of frogfish species in Hawaiian waters, this is the one seen most often -- possibly because it is easier to see than the others! Most of the other frogfish species are so well camouflaged that they're almost impossible to spot.

This funny looking little guy is a frogfish. More precisely, this species is Commerson's Frogfish (Antennarius commerson). Although there are a number of frogfish species in Hawaiian waters, this is the one seen most often -- possibly because it is easier to see than the others! Most of the other frogfish species are so well camouflaged that they're almost impossible to spot.The color of frogfishes is extremely variable; they generally match their surroundings very well. If the background color is changed, they may in a few weeks dramatically change color, as from red or yellow to black.*Pretty good trick!

BNSullivan.jpg) Basic diver certification courses all include instruction on air sharing. (For our non-diving readers, 'air-sharing' refers to more than one diver using the same air source.) This is a very basic and essential skill, and these days it is also quite easy, in principle.

Basic diver certification courses all include instruction on air sharing. (For our non-diving readers, 'air-sharing' refers to more than one diver using the same air source.) This is a very basic and essential skill, and these days it is also quite easy, in principle.BNSullivan.jpg)

BNSullivan.jpg) Judging from our traffic statistics, a lot of people look on the worldwide web for information about sharks and photos of these predator fish. The word 'shark' and phrases containing that word always are among the top keywords that bring search traffic to The Right Blue, month after month.

Judging from our traffic statistics, a lot of people look on the worldwide web for information about sharks and photos of these predator fish. The word 'shark' and phrases containing that word always are among the top keywords that bring search traffic to The Right Blue, month after month. From time to time, one of our readers writes about one of our articles or photos and links to The Right Blue. Some of our fellow bloggers have given awards to The Right Blue. We list all of these on our blogroll page, but we admit we're not very good about passing them along.

From time to time, one of our readers writes about one of our articles or photos and links to The Right Blue. Some of our fellow bloggers have given awards to The Right Blue. We list all of these on our blogroll page, but we admit we're not very good about passing them along. In addition, we'd like to recognize artist Carol Cooper who wrote a thoughtful piece on her blog, Compass WebWorks, about how photographers help all of us to see things in the world that we might otherwise not see, except Through Their Eyes. To illustrate her point, Carol used a macro photo of Bubble Coral, by Bobbie.

In addition, we'd like to recognize artist Carol Cooper who wrote a thoughtful piece on her blog, Compass WebWorks, about how photographers help all of us to see things in the world that we might otherwise not see, except Through Their Eyes. To illustrate her point, Carol used a macro photo of Bubble Coral, by Bobbie. We thank these blogger friends for thinking of us in such a positive way and expressing it. We also would like to thank all of our subscribers and regular readers, especially those who participate interactively with us by asking questions and leaving comments. Included in that group are the many participants in the Wordless Wednesday and Watery Wednesday photo memes who stop by each week.

We thank these blogger friends for thinking of us in such a positive way and expressing it. We also would like to thank all of our subscribers and regular readers, especially those who participate interactively with us by asking questions and leaving comments. Included in that group are the many participants in the Wordless Wednesday and Watery Wednesday photo memes who stop by each week.BNSullivan.jpg) Today we present the next example of 'Exotic Underwater Nudies' -- our series on nudibranchs (a.k.a. sea slugs) from around the world. This particular nudibranch lives primarily in the Mediterranean Sea. Its usual common name is the Dotted Sea Slug. Its scientific name is Peltodoris atromaculata -- but it used to be called Discodoris atromaculata. More on this below.

Today we present the next example of 'Exotic Underwater Nudies' -- our series on nudibranchs (a.k.a. sea slugs) from around the world. This particular nudibranch lives primarily in the Mediterranean Sea. Its usual common name is the Dotted Sea Slug. Its scientific name is Peltodoris atromaculata -- but it used to be called Discodoris atromaculata. More on this below.BNSullivan.jpg) The second photo shows the underside of this creature. (Yes, I flipped it over on purpose so that I could photograph its underpinnings, but I then returned it to its original position before I swam away.) You can see the creature's 'foot' -- the muscular structure that it uses for locomotion -- and you can see how the mantle extends like a skirt to obscure the foot when the animal is in its normal position.

The second photo shows the underside of this creature. (Yes, I flipped it over on purpose so that I could photograph its underpinnings, but I then returned it to its original position before I swam away.) You can see the creature's 'foot' -- the muscular structure that it uses for locomotion -- and you can see how the mantle extends like a skirt to obscure the foot when the animal is in its normal position.BNSullivan.jpg) Now, about the name. Regular readers of The Right Blue know by now that we like to give the scientific names of the critters we write about or show in our photos, because common names often vary from one location to the next, and certainly from one language to the next, while the scientific name is standardized: it is the same for a given species across languages and locations. When we know and use a creature's scientific name, we can be sure that we are all talking about the same thing.

Now, about the name. Regular readers of The Right Blue know by now that we like to give the scientific names of the critters we write about or show in our photos, because common names often vary from one location to the next, and certainly from one language to the next, while the scientific name is standardized: it is the same for a given species across languages and locations. When we know and use a creature's scientific name, we can be sure that we are all talking about the same thing.BNSullivan.jpg) For the past few months, virtually all of our posts here on The Right Blue have focused on interesting species of marine life we have come to know. Feedback on those articles has been positive: our readers seem to enjoy learning about creatures that inhabit the sea. But we also have been nudged by a few readers to get back to writing about diving -- as in, "Enough with the critters, already. Get back to diving stories!"

For the past few months, virtually all of our posts here on The Right Blue have focused on interesting species of marine life we have come to know. Feedback on those articles has been positive: our readers seem to enjoy learning about creatures that inhabit the sea. But we also have been nudged by a few readers to get back to writing about diving -- as in, "Enough with the critters, already. Get back to diving stories!"BNSullivan.jpg) The best way to prevent many of these inadvertent stings and scrapes is to wear a full suit that covers you from your wrists to your ankles. Wear boots or neoprene booties inside your fins. And wear gloves.

The best way to prevent many of these inadvertent stings and scrapes is to wear a full suit that covers you from your wrists to your ankles. Wear boots or neoprene booties inside your fins. And wear gloves.BNSullivan.jpg) This is the third article in our series on 'Exotic Underwater Nudies', i.e., nudibranchs. We began the series last month with the Spanish Dancer, exceptional for its large size and unique swimming behavior. Next we presented the lovely Gold Lace nudibranch, a species endemic to Hawaii. Today we'll take a look at a very different kind of nudibranch -- different both in form, and in how it makes its living.

This is the third article in our series on 'Exotic Underwater Nudies', i.e., nudibranchs. We began the series last month with the Spanish Dancer, exceptional for its large size and unique swimming behavior. Next we presented the lovely Gold Lace nudibranch, a species endemic to Hawaii. Today we'll take a look at a very different kind of nudibranch -- different both in form, and in how it makes its living.BNSullivan.jpg) The Blue Dragon stores zooxanthellae in its cerata -- those fluffy looking bits that cover its body. In fact, one hypothesis about the Blue Dragon's form posits that the cerata may have evolved in order to provide more surface area for the zooxanthellae to inhabit. More surface area means more space for zooxanthellae, as well as a greater likelihood that they will be exposed to the light they need for photosynthesis.

The Blue Dragon stores zooxanthellae in its cerata -- those fluffy looking bits that cover its body. In fact, one hypothesis about the Blue Dragon's form posits that the cerata may have evolved in order to provide more surface area for the zooxanthellae to inhabit. More surface area means more space for zooxanthellae, as well as a greater likelihood that they will be exposed to the light they need for photosynthesis.BNSullivan.jpg) Earlier this week, for Wordless Wednesday, I posted a photo of a Napoleon Wrasse. Readers commented on the size of the fish, on its shape, and on its prominent eye.

Earlier this week, for Wordless Wednesday, I posted a photo of a Napoleon Wrasse. Readers commented on the size of the fish, on its shape, and on its prominent eye.BNSullivan.jpg) These fish can live for thirty years or so, and they seem to have long memories. When we first began to dive in the Red Sea a few decades ago, dive guides there sometimes would entertain their clients by hand feeding boiled eggs to the Napoleon Wrasses. After awhile, once everyone finally realized that this was not an ecologically sound thing to do, this practice was banned.

These fish can live for thirty years or so, and they seem to have long memories. When we first began to dive in the Red Sea a few decades ago, dive guides there sometimes would entertain their clients by hand feeding boiled eggs to the Napoleon Wrasses. After awhile, once everyone finally realized that this was not an ecologically sound thing to do, this practice was banned.BNSullivan.jpg) Along came a Napoleon. It saw the round white shape cupped in our friend's hand and apparently mistook it for an egg. First the fish swam back and forth excitedly around our friend. Then it nudged him. Annoyed, our friend put out one hand to push the aggressive fish away. At that instant, the Napoleon lunged and snapped the white regulator out of our friend's other hand -- or tried to. The regulator was attached to a hose, of course. When the Napoleon bit, the hose partly detached and it began to froth like crazy from the rapidly escaping compressed air. That scared the fish, which went zooming past us with our friend's glove hanging from its mouth!

Along came a Napoleon. It saw the round white shape cupped in our friend's hand and apparently mistook it for an egg. First the fish swam back and forth excitedly around our friend. Then it nudged him. Annoyed, our friend put out one hand to push the aggressive fish away. At that instant, the Napoleon lunged and snapped the white regulator out of our friend's other hand -- or tried to. The regulator was attached to a hose, of course. When the Napoleon bit, the hose partly detached and it began to froth like crazy from the rapidly escaping compressed air. That scared the fish, which went zooming past us with our friend's glove hanging from its mouth!