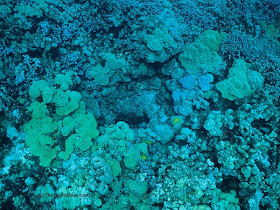

What: A soothing image of a tropical coral reef.

Where: I took this photo while diving at Bunaken Island, Indonesia.

BNSullivan.jpg)

Click on the photo to enlarge so you can see all the different types of corals.

BNSullivan.jpg) The Big Island of Hawaii, where we live, is volcanically active. Kilauea Volcano, in the southern part of the island, has been erupting continuously since 1983, sending lava down its flank and into the ocean. Mauna Loa, another active volcano on the island, erupted most recently in 1984, and could erupt again at any time.

The Big Island of Hawaii, where we live, is volcanically active. Kilauea Volcano, in the southern part of the island, has been erupting continuously since 1983, sending lava down its flank and into the ocean. Mauna Loa, another active volcano on the island, erupted most recently in 1984, and could erupt again at any time.BNSullivan.jpg) It was the unexpected interruption of the field of finger coral that first caught our eye. We swam over to have a better look at these anomalies, and that's when we discovered that the crusty looking corals actually were arrayed around holes in the reef. When we hovered directly over the holes to peer inside, we felt the warm water emanating from below. We understood right away that these holes were venting geothermally heated water. It was an exciting find.

It was the unexpected interruption of the field of finger coral that first caught our eye. We swam over to have a better look at these anomalies, and that's when we discovered that the crusty looking corals actually were arrayed around holes in the reef. When we hovered directly over the holes to peer inside, we felt the warm water emanating from below. We understood right away that these holes were venting geothermally heated water. It was an exciting find.BNSullivan.jpg) In this final photo, at left, our friend Dan is poking his head and shoulders into the larger of the two vents. I had asked him to pose for a photo near the mouth of the vent, to provide a reference for the size of the opening. Dan decided spontaneously that this posture would demonstrate the size better than simply posing beside it! (Thanks, Dan.)

In this final photo, at left, our friend Dan is poking his head and shoulders into the larger of the two vents. I had asked him to pose for a photo near the mouth of the vent, to provide a reference for the size of the opening. Dan decided spontaneously that this posture would demonstrate the size better than simply posing beside it! (Thanks, Dan.)BNSullivan.jpg)

BNSullivan.jpg)

BNSullivan.jpg) Over the years we have become quite adept at finding shells underwater, but some species that we wanted for our collection were elusive for a long time. There were some we had seen in books or displays that we just never came across in the ocean. In other cases we had found the shell, sometimes on numerous occasions, but only ones that still had the critter living inside.

Over the years we have become quite adept at finding shells underwater, but some species that we wanted for our collection were elusive for a long time. There were some we had seen in books or displays that we just never came across in the ocean. In other cases we had found the shell, sometimes on numerous occasions, but only ones that still had the critter living inside.BNSullivan.jpg) Here's a special cowrie shell from our collection. The shell pictured at right is an Arabian Cowrie (Cypraea arabica). Jerry found this one in the Red Sea many years ago, and it is the only one we've ever seen, except in pictures.

Here's a special cowrie shell from our collection. The shell pictured at right is an Arabian Cowrie (Cypraea arabica). Jerry found this one in the Red Sea many years ago, and it is the only one we've ever seen, except in pictures.BNSullivan.jpg)

BNSullivan.jpg)

BNSullivan.jpg) In a recent post, we introduced our readers to Cone Shells, and the snails that make those shells and live in them. We mentioned that the Cone Shell snails have a venomous sting, making them potentially dangerous to handle when they are alive.

In a recent post, we introduced our readers to Cone Shells, and the snails that make those shells and live in them. We mentioned that the Cone Shell snails have a venomous sting, making them potentially dangerous to handle when they are alive. BNSullivan.jpg) The Striated Cone is one of the Cone Shell species considered to be potentially dangerous to humans. For one thing, its venom is among the most potent. For another, the snail is amazingly flexible and agile. Its siphon and proboscis (where the stinging radula teeth are located) can be extended nearly the length of its shell. Thus, even if you are careful to hold a live Striated Cone Shell by the widest end, it still may be possible for it to sting you.

The Striated Cone is one of the Cone Shell species considered to be potentially dangerous to humans. For one thing, its venom is among the most potent. For another, the snail is amazingly flexible and agile. Its siphon and proboscis (where the stinging radula teeth are located) can be extended nearly the length of its shell. Thus, even if you are careful to hold a live Striated Cone Shell by the widest end, it still may be possible for it to sting you.